A New Paradigm for Brand Trust

Why even the most storied companies will have to re-examine their approach.

Rob Peckerman is a brand and communications strategist. He is a strategy director at Wunderman Thompson and Long Dash alum.

Author Jim Collins once wrote that “greatness is not a function of circumstance. Greatness, it turns out, is largely a matter of conscious choice, and discipline.” Today’s brands—large or small, across any industry—face a constantly changing set of circumstances, each posing its own challenge. Those seeking to endure need to have a strategy in place. Specifically, they need to make a conscious choice and take a disciplined approach to fortifying the cornerstone of all effective brand strategies: consumer trust.

As brands are increasingly subject to the whims of consumer choice, market forces, and public opinion, trust has become the centerpiece of many brand and marketing strategies. Brands facing these heightened expectations from consumers have been grappling with the challenge of building and deepening trust among an increasingly skeptical audience. As they have, however, the concept of building trust has become so ubiquitous it is almost vacuous—many investments in building trust under-appreciate its complexity; or, equally limiting, underestimate the resources necessary to earn it.

As COVID-19 overtakes the nation, many brands still on solid footing are shifting their strategies to strengthen trust with people. People around the world are struggling to keep a steady income, protect their families, and maintain a sense of normalcy; and, as they are, they are increasingly looking to any organization—public or private—to create clarity, direction, and order out of chaos. The brands that have prioritized service, empathy, and trust in this moment are the ones that will fill this gap for people and thrive after this crisis is over.

Yet, it is important to remember that trust is built over time, not in response to a crisis. It is a product of careful planning, not risk mitigation. As such, COVID-19 is a signal moment that will require brands to redefine how they build trust with people, not just today, but for months and years to come. It is a reminder that, instead of being monolithic, trust is a progressive hierarchy of understanding between brands and the people they serve. COVID-19, through the historic uncertainty and devastation it has unleashed, is making these hierarchies apparent.

The typical playbooks and “business as usual” strategies will no longer suffice. Instead, the great brands will distinguish themselves from the good (and from the forgotten) not only by meeting audiences’ basic needs for products and services, but also by connecting with them on a deeper, emotionally aligned level.

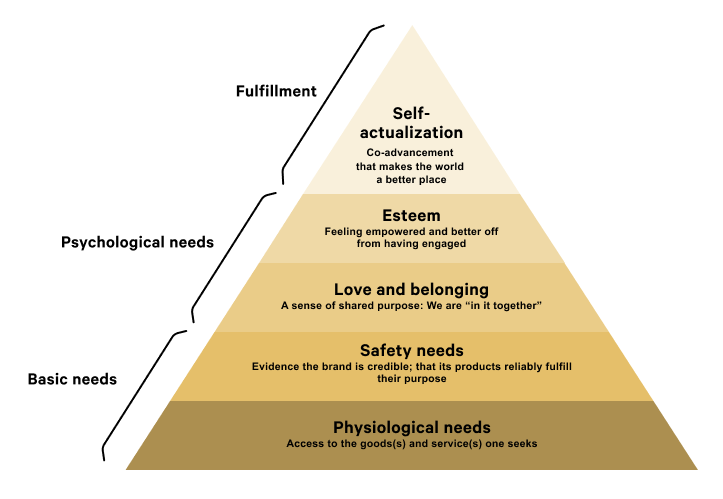

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

This expectation is rooted in a hierarchy most akin to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

Maslow’s hierarchy identifies five overarching needs that motivate people and posits that each need—from the most basic to most profound—must be fulfilled before humans are motivated to fulfill the next. At the base of the pyramid, Maslow suggests, are physiological needs (e.g., food, shelter, sleep, clothing), which, once met, motivate us to meet our safety needs (e.g., employment, health, property). Once these more basic needs are fulfilled, Maslow suggests we seek out psychological needs such as love and belonging (e.g., friendship, intimacy, sense of connection), and then esteem (e.g., respect, recognition, status). Finally, once each of these prerequisite needs is met, we pursue the very top of the pyramid, self-actualization (i.e., to become the most that one can be).

For brands, there is a parallel hierarchy and prioritization. The most successful brands will move people up the hierarchy over time. To do this, brands must demonstrate to consumers that they will continually find greater value in moving up the pyramid with them. The brands that do this will have the most staying power and will have a stronger chance of emerging from this crisis with trusted consumer relationships.

Hierarchy of Brand-Consumer Relationships

At the base of this brand-consumer relationship hierarchy are one’s individual, basic needs. People need access to the products and services brands provide. Only with that need met are they able to then prioritize brands that can more reliably, safely, and credibly deliver the products they seek. For most people, this is a transactional, convenience-driven calculus. But it is also a poignant reminder that if your brand does not meet these needs, nothing else you say or do will matter.

Once these foundational needs are fulfilled, people can begin valuing brands that address their psychological needs. This includes feeling empowered and better off from having engaged with a brand, as well as having a sense of shared purpose. In crowded and competitive markets, this is where brands can distinguish themselves and cultivate audience loyalty.

Finally, once each of these prerequisite needs is met, brands can further set themselves apart by providing for the very top of the pyramid: fulfillment. At this stage, people engage with a brand to give back to the world and make it a better place. The data is clear, especially among Millennial and Gen Z audiences: Demonstrating social impact is a critical driver of consumer engagement and employee morale. Fulfillment, however, is more than that. It is not about designing a high-quality annual CSR report, which everyone else is now doing and most people aren’t reading. It is the pursuit of a shared aspiration that is greater than the brand or consumer.

Brands should view this relationship hierarchy as a way to interpret the current moment. The threat of COVID-19 has skyrocketed demand for products that address people’s core physiological and safety needs (e.g., food, cleaning goods). Almost overnight, people have been forced to prioritize safe working conditions and job security above all else, as others have had to focus on access to food and health care.

Meanwhile, demand for nonessential goods and services has plummeted. People are still hungry to have social and psychological needs met, but many cannot address these needs until their more immediate, basic needs are satisfied. For many brands, the ability to navigate this moment hinges on the ability to understand which needs they are best-positioned to address—and then deliver on them.

Thus far, they have demonstrated varying degrees of success doing so. Some brands have made misguided efforts to maintain demand for products that consumers cannot prioritize. For example, while many people feared for their health and physical safety, businesses like WeWork, Tesla, and Adidas were almost defiant in their unwillingness to close down their offices, putting their employees at risk. Adidas went so far as to argue “closing is easy, staying open requires courage”—a position they walked back less than 24 hours later following public outcry.

Conversely, some brands with products in high demand initially made decisions to focus their attention elsewhere. For example, Popeyes chose to raffle off its Netflix username and password rather than double down on making chicken sandwiches. While the campaign correctly assumed people would be spending more time watching TV, it was misaligned with what the brand is best-positioned to offer and what people needed from it at that moment. Meanwhile, a Seattle-based Target store was found selling medical masks, even as local public health workers reported shortages at hospitals.

Brands that have ensured people’s new basic needs were met before seeking to meet their other needs have generally been applauded. Patagonia, for example, was one of the first brands to close its stores, citing public health concerns. This was a critical early action to meet employees’ and consumers’ basic health safety needs. At the same time, it redirected customers to visit its online food store, Patagonia Provisions, to explore its sustainably sourced meals. Meanwhile, a laundry list of brands—among them Anheuser-Busch, Dyson, Ford, Gap, and LVMH—have been quick to convert their facilities to hand sanitizer, ventilator, and/or mask and scrubs production. Food service brands like Sweetgreen, KFC, and &Pizza have likewise been lauded for offering free meals and delivery to hospital staff and frontline workers.

The brands that build the most trust during this time are likely to be those that not only met basic needs first, but then also met other needs up the hierarchy. Nike understood that demand for its consumer products was likely to diminish during this time and sought to provide value elsewhere. The brand was quick to announce it would donate $15 million to various response efforts and later began creating personal protective equipment to support frontline workers. The brand also found ways to ensure that, even in times of crisis, its audiences could feel empowered, launching a campaign not to sell sneakers, but to encourage social distancing. It leveraged global icons like LeBron James, Serena Williams, and Cristiano Ronaldo to tell audiences, “Play inside, play for the world.” The message was clear: We are in this together, and with your help, we can make the world a better place.

Sign up for OnBrand

Our weekly digest featuring ideas on the future of brand.

However, brands that do not understand these different levers of trust and how they interplay with one another—or have failed to address them—are likely to struggle. To succeed in the long run, brands should master these different levers of trust, how audiences move across them, and how they build on one another. Below are three recommendations for how brands can do this:

1) Build Trust Across the Entire Hierarchy

The best way to ensure a nimble response to a changing situation is to have a trust-building strategy in place before the moment strikes. Otherwise, brands navigating ongoing change may find themselves feeling like the proverbial “leaking boat”—if they invest all their resources in bailing water from the boat, none are left to steer away from the iceberg looming ahead. A trust-building strategy should address each stage of the hierarchy of needs, and it should tie into a brand’s overall goals and positioning. The idea is for the brand to remain true to itself and its core purpose across every consumer-facing (and employee-facing) initiative. A strategy should articulate what people expect from the brand at each level of the hierarchy and define key messages and tactics for the brand at each stage. Brands that have a strong, considered foundation will find it easier to pivot and make adjustments as market forces and consumer demands evolve.

2) Be Ready to Pivot to Different Parts of the Hierarchy

Throughout the current crisis, people’s emotions have understandably varied, from frightened to angry, overwhelmed, lonely, hopeful. People are also experiencing these emotions through their identities as individuals, family members, employees, and members of society. The most successful brands in this moment understand this complexity and have channeled their response to focus on the portions of the hierarchy that are most relevant to their audiences. Not only do brands need to identify the right part of the hierarchy at the right moment, but they also need to communicate with empathy and sincerity to prove the authenticity of their words. Brands should adopt a nimble and curious listening posture that is backed by an organizational capacity to pivot and execute on different parts of the hierarchy as people demand them.

3) Appreciate the Expectations Delta

To build trust and strengthen brand perceptions, brands need to deliver against the expectations of their customers—and they need to do it exceptionally well. The greater the delta between what people expect and what you deliver, the greater the impact on brand trust. MillerCoors, for example, was initially recognized for donating $1 million to a nonprofit serving bartenders, but then criticized online after many felt they could or should do more. Meanwhile, fitness brands such as Barry’s Bootcamp, CorePower Yoga, Orangetheory, and [Solidcore] have earned strong praise within fitness communities for unexpectedly launching free, online, home-oriented classes even as their studio doors closed. For brands to grow, they need not spend the most money or be the hero in absolute terms. Instead, they need to exceed expectations in relative terms, in ways that align with their brand and the moment in which they are acting. The key is for a brand to understand the specific expectation their audiences have of them and to consistently over-deliver on that expectation. Trust, loyalty, and reputational growth will come when brands continue to exceed those expectations over time.

While it remains too early to predict exactly how this crisis will end, the brands that understand and address this hierarchy will be best-positioned to grow and recover when the world stabilizes. The hierarchy is a tool brands can use to more deliberately evaluate the challenges they and their audiences face and more strategically select a course of action. Building team awareness of this framework over time and empowering employees to act on it will enable brands to serve as a beacon of hope in times of crisis and to carve out paths toward stability and growth for years to come.